The management consulting firm McKinsey & Co. has acknowledged a commercial connection to “the Chinese government,” according to a court document, even though the firm told a U.S. senator it had no business ties to the Beijing regime.

According to Sen. Marco Rubio, R.-Fla., McKinsey told the lawmaker in July 2020 that it did not work with the Chinese government or the ruling Chinese Communst Party. Company executives repeated that assertion in a Zoom conference call in March this year with Sen. Rubio’s advisers, according to the senator.

But in a bankruptcy case involving the offshore drilling firm Valaris, in which McKinsey applied to act as an adviser, the consulting firm disclosed a commercial connection to the “Chinese government,” according to a September 2020 court document.

Rubio had demanded the firm share more information about its work in China and explain how it prevents conflicts of interest between its consulting business for the U.S. government and Chinese clients close to the Beijing government.

In a letter Thursday to McKinsey obtained by NBC News, the senator expressed outrage over the episode and accused the firm of misleading him about its activities in China.

“It has come to my attention that McKinsey & Company appears to have lied to me and my staff on multiple occasions regarding McKinsey’s relationship with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Chinese government,” Rubio wrote.

Rubio said McKinsey’s work with the Chinese government as well as state-owned enterprises, coupled with its consulting for U.S. federal agencies, poses “serious institutional conflicts of interest.”

“It is increasingly clear that McKinsey & Company cannot be trusted to continue working on behalf of the United States government, including our Intelligence Community.”

A McKinsey spokesperson said the company did not perform work for the Chinese central government but only for provincial and local governments in China, and that the company had made that clear in previous correspondence with Rubio’s office.

“We have been consistent and transparent in all of our communications with Sen. Rubio’s office,” the spokesperson told NBC News. In its July 2020 letter with Rubio, McKinsey had said a small portion of its work in China was with local and provincial governments related to economic zones, urban planning and real estate, the spokesperson said.

The disclosure in the bankruptcy case “reflects an accurate description of client service that includes local and provincial government, and is entirely consistent with the type of work we communicated openly about with the Senator’s office,” the spokesperson said. “In no way does it refer to work for the Central Government, Communist Party of China or the Central Military Commission of China, none of which are clients of McKinsey, and to our knowledge, have never been clients of McKinsey.”

The bankruptcy disclosure cites the “Chinese government” and does not specify whether the client is the provincial or central government.

Analysts say that Chinese state-owned enterprises like the ones McKinsey has worked with have Chinese communist party officials embedded in the top layers of leadership.

A McKinsey spokesperson told NBC News last month that the company’s policy bars work with political parties.

“We do not serve political parties anywhere in the world,” the McKinsey spokesperson said.

According to Rubio, in a July 3, 2020 letter in response to his inquiry, Liz Hilton Segel, the managing partner for McKinsey’s North America operations, wrote that to “our knowledge, [neither the Chinese Comunist Party nor the Chinese government] has ever been a client of McKinsey.”

During a Zoom conversation on March 17, 2021, “members of McKinsey’s worldwide leadership team once again told my staff that they had no knowledge of the CCP or the Chinese government having ever been a client,” Rubio wrote.

“As you well know, any dealings with the Chinese government are necessarily dealings with the CCP,” Rubio wrote.

NBC News previously reported that McKinsey has carried out sensitive consulting for the Pentagon and U.S. intelligence agencies while also performing work for powerful state-owned enterprises in China supporting Beijing’s military buildup. The company’s work in China has drawn growing scrutiny from lawmakers, who say it poses a potential conflict of interest that could jeopardize U.S. national security.

McKinsey’s consulting contracts with the federal government give it an insider’s view of U.S. military planning, intelligence and high-tech weapons programs. But the firm also advises Chinese state-run enterprises that have supported Beijing’s naval buildup in the Pacific and played a key role in China’s efforts to extend its influence around the world, according to lawmakers, experts and federal officials.

McKinsey says it abides by U.S. laws on federal contracting and that it has extensive internal rules to prevent conflicts of interest and to protect clients’ information.

Critics like Rubio say the firm, the world’s largest consulting company, needs to divulge more details about its work in China, particularly amid concerns in Washington about Beijing’s industrial espionage, arms buildup and intellectual property theft.

In a November 2020 letter to McKinsey, Rubio said he was concerned the company “either wittingly or unwittingly — is aiding the Chinese Communist Party’s attempt to supplant the United States.”

In the same bankruptcy case involving the firm Valaris, McKinsey also disclosed its ties to Shenzhen Dajiang Baiwang Technology Co, a manufacturing facility specializing in unmanned aerial vehicles and owned by Chinese drone maker DJI.

On Thursday, the U.S. Treasury Department said it will add DJI along with seven other Chinese firms to an investment blacklist linked to the “Chinese military industrial complex.”

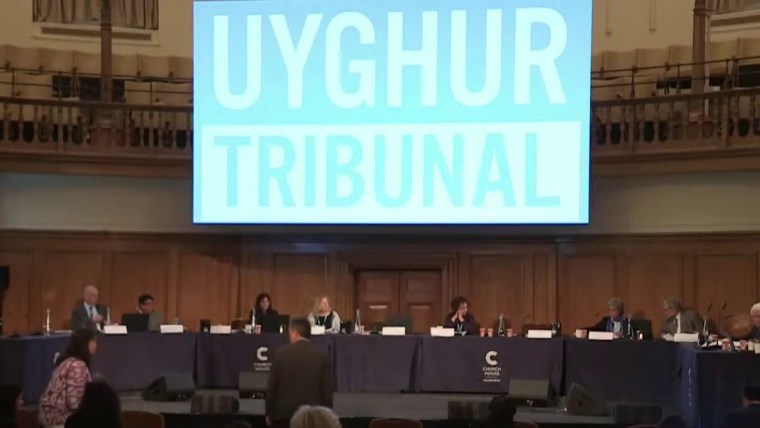

The Treasury Department said DJI “has provided drones to the Xinjiang Public Security Bureau, which are used to surveil Uyghurs in Xinjiang.”

Apart from its consulting in China, McKinsey has come under sharp criticism from lawmakers and faced legal challenges over alleged conflicts of interest in other fields.

This year, without admitting to wrongdoing, the company agreed to pay $573 million to settle allegations from 49 states that its work for opioid manufacturers helped “turbocharge” sales of the drugs, contributing to a deadly addiction epidemic. At the same time the firm was working for the pharmaceutical companies, McKinsey was advising the Food and Drug Administration on its prescription drug policy, according to court documents.

Last month, a multi-billion-dollar private investment fund affiliated with McKinsey & Co. settled regulatory allegations that it did not have adequate policies in place to prevent the misuse of inside information gleaned from its vast corporate consulting business, according to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Although the S.E.C. did not claim the fund actually misused confidential information, it cited the dual roles played by McKinsey partners who oversaw the massive fund’s investment choices even as they had access to nonpublic client information.

The McKinsey investment fund, known as MIO Partners, agreed to pay $18 million to settle the matter, neither admitting nor denying the allegations. In striking the settlement, MIO said in a statement, “The historical issues identified in the S.E.C. order have been resolved by MIO through strengthened policies and procedures, and the order does not identify any misuse of confidential or material non-public information by either MIO or McKinsey.”